Goldsmith Chandlee

History

Goldsmith Chandlee

Dr. Richard L. Elgin, LS, PE

Goldsmith Chandlee was one of the most notable American clock and instrument makers of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Born August 18, 1751 in Nottingham, Maryland, Goldsmith was the oldest son of Quaker clockmaker Benjamin Chandlee, Jr. (1723-1791) and Mary Folwell Chandlee (died 1806). He was named for his maternal grandfather, Goldsmith Folwell. Of Irish descent, Goldsmith's grandfather was Benjamin Chandlee, Sr. (1685-died c. 1745), known as "the emigrant" who came to Philadelphia from Ireland in 1702.

Characterized as the "Six Quaker Clockmakers" in a 1943 book by that title, the first of the six clockmakers was Abel Cottey (1655-1711). He probably built the first clock in America. A clock, marked "Abel Cottey, Philadelphia" is dated 1709. One of his apprentices and Cottey's future son-in-law was Benjamin Chandlee, Sr. ("the emigrant"), the second Quaker clockmaker. Benjamin, Sr. had six children, one of them being Benjamin, Jr., the third Quaker clockmaker. Benjamin, Jr. had five children, three of which became clock and instrument makers: Goldsmith, Ellis, and Isaac Chandlee. These brothers are considered the fourth, fifth, and sixth Quaker clockmakers.

Goldsmith apprenticed under his father in Nottingham, Maryland and by the time he was 24 years old he was an experienced craftsman. In 1775 he moved to Stephensburg (now Stephens City), Virginia and then on to Winchester, Virginia in 1783. There he built a brass foundry and a shop where he produced clocks, surveying compasses, telescopes, money scales, and other instruments of metal. His business was located on the northwest corner of Cameron and Piccadilly Streets where he owned several buildings and also resided. Besides making clocks and compasses, he was active in many civic activities. He was a member of the volunteer fire company; was a justice of the Corporation of Winchester; sat on the Bench of Justice of Hastings Court of that city; and he drafted deeds, mortgages, and various legal papers; and acted as executor of estates. He was recognized as a leader in financial circles in northern Virginia and established a counting house in which he bought and sold bills of exchange, bonds, notes, soldiers' certificates, and military warrants. He also dealt in land and owned large tracts of land in Pennsylvania, Virginia, and Kentucky.

Goldsmith married three times. He first married in 1776 Ann White (died 1781). From this union came three children, one being Benjamin III (1780-1822) who also was an instrument maker. In 1784, Goldsmith married Hannah Yarnall (1750-1810). From this union came four children, one being Goldsmith, Jr. (1788-1842). In 1811, Goldsmith married Eunice Allen (1753-1822). They had no children.

Technically Advanced Compasses

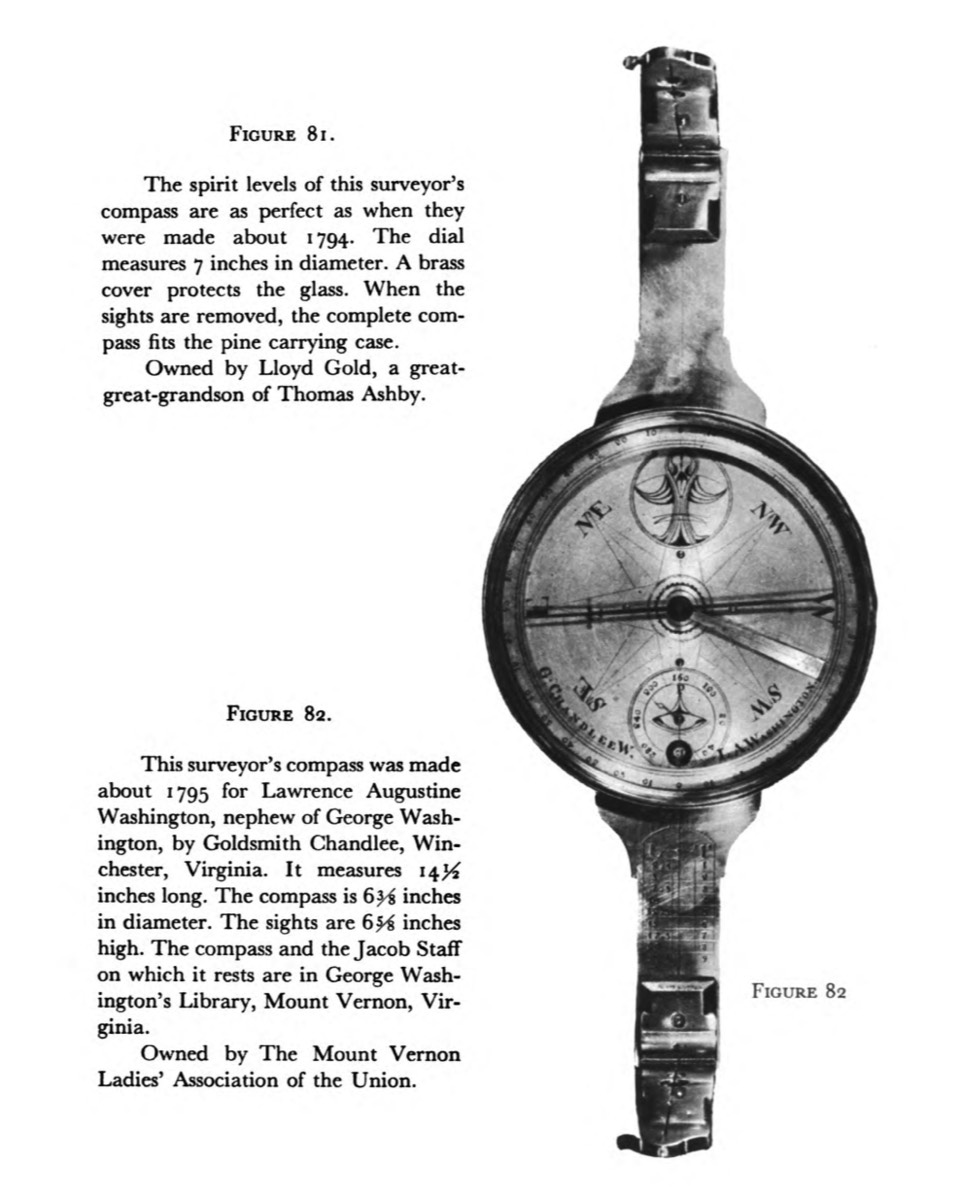

Goldsmith Chandlee must be counted as one of the most notable American compass makers. His compasses are works of art and were technically advanced. The compass faces show fine design, craftsmanship, engraving and ornate decoration. Technically his compasses were the most advanced of their day. He made both plain and vernier compasses. All but one of the known Goldsmith Chandlee compasses have his "L" and "T" table (for converting tenths of perches to links and vice versa). All known Goldsmith Chandlee compasses also have an outkeeper and dial that converts outs to poles, the invention of which (or its application to a compass) we can attribute to him. Some of his compasses also have a counter where the surveyor could tally the miles chained. All known Goldsmith Chandlee compasses are marked with at least "G. Chandlee," with that inscription being followed with "Winchester" or "W" (for what today is Winchester, Virginia). Most Goldsmith Chandlee compasses also are marked (following the lettering given above) with the name of the person for whom the compass was made. Probably the most notable person for whom Chandlee made a compass (but not the most elaborate known Chandlee compass) was Laurence Augustine Washington, nephew of another surveyor, George Washington. That compass is displayed at Mount Vernon.

Compass Production Records Not Available

Goldsmith has been described as a small, sparse man with dark brown hair. He is said to have been fond of company and "much given to entertaining." He died in Winchester on March 4, 1821 and was buried in Center Meeting graveyard on the Valley Pike. After his death his personal property was sold at auction. Sixty-six items, mostly tools, compasses, clocks, and compass parts were purchased by his apprentice, George Graves (1792-1873). There are only a few known Graves compasses, and they have the same features as the Goldsmith Chandlee compasses. (Goldsmith's son, Benjamin III, also was an instrument maker. His known compasses have the same features as his father's.) In the 1950s, Goldsmith Chandlee's body was relocated to the Hopewell Centre Meeting graveyard north of Winchester where his grave is today marked with a simple headstone marked "G. Chandlee."

Collectors and researchers are always curious as to how many compasses Goldsmith Chandlee may have produced. There are no known Goldsmith Chandlee production records and his compasses are not numbered. Through various sources, the author knows of sixteen Goldsmith Chandlee compasses, although he probably made many more.

Goldsmith Chandlee's Outkeeper

Goldsmith Chandlee placed an outkeeper on his compasses like none other. But first, what's an out? "Out!" is what the head chainman yells when he is out of chaining pins. Perhaps I should digress. Chaining is performed using eleven chaining pins. When a distance is to be measured, the head chainman starts off with ten chaining pins on a ring. The eleventh pin is used to mark the beginning point of the distance to be measured. The rear chainman has no pins on his chaining pin ring. The distance of the chain or tape is laid off, the head chainman placing a chaining pin from his ring at the end (or some mark) of his chain, and yells "Stuck!" when the chaining pin is in the ground. On hearing "stuck" the rear chainman pulls his chaining pin and places it on his ring. Once the chain is again ready (straight, pulled tight, horizontal) the rear chainman yells "Good!" and the head chainman places another chaining pin in the ground and again yells "Stuck!" Again, on hearing that, the rear chainman pulls his chaining pin and places it on his ring. And so the chaining progresses. Note that using this procedure, the number of chain units measured, or, the location of the chaining pin in the ground, equals the number of chaining pins the rear chainman has on his ring. For example, if the crew is using a 66-foot chain and the rear chainman has eight chaining pins on his ring, then the pin in the ground is at eight chains from the beginning point. The chaining progresses until, after sticking the last chaining pin on his ring, the head chainman yells "Out!" (out of chaining pins) which is an explanation of the "out" mentioned above. It's ten pulls of the tape or chain, whatever is its length.

The early instructions for the survey of the public lands called for the use of a two-pole chain (33 feet). An "out" (ten pulls) would therefore be 20 poles (330 feet). The usual outkeeper found on most compasses by practically all makers, from the late 1700s until as late as the 1940s, shows the integers 1 through 16. As the head chainman yelled "Out!", the compassman clicked the outkeeper another unit until the number 16 was reached. At that point the chainman had measured 16 outs, or, if using a two-pole chain, 320 poles (2 poles x 10 x 16), or one mile.

Goldsmith Chandlee was not satisfied with an outkeeper that merely counted from 1 to 16. He apprenticed to his father, Benjamin, Jr. who was a noted clock and instrument maker. Because Goldsmith was a clockmaker himself, the development of an elaborate outkeeper was easily within his ability.

The outkeeper that Goldsmith Chandlee invented and developed had no equal. Chandlee's outkeeper is operated from the bottom of the compass. As the knob is advanced, the integers 1 through 16 can be viewed through a window as seen from above the compass. At the same time the knob advanced, a pointer or hand moved to point to the numbers 0 through 320, engraved on the face of a dial in 20-unit increments. So, as the number of "outs" is counted from 1 through 16, the dial/hand arrangement converted the "outs" to poles. Thus we had our first automatic data collector, which is so popular in today's electronic/computerized world of surveying.

No other maker used this advanced form of outkeeper, and we may be able to attribute the invention of the outkeeper in general to Chandlee. An informal examination by the authors of known early (pre-1800) American compasses shows only Goldsmith Chandlee placing an outkeeper on a compass—with one exception: there is a Benjamin Rittenhouse compass which is dated 1786 that has a simple 1-16 outkeeper. Chandlee began crafting compasses somewhere between 1775 to 1783.

Actually, Goldsmith Chandlee had two forms of outkeepers or counters on some of his compasses. One, as described above, which is labeled with a prominent "P" (poles) on its dial. The other is a more simple dial operated by a knob (on the underside of the compass) that turned a hand on the compass face. The dial, prominently marked "M" (miles) is graduated in single units from 0 through 21, and is marked in units of 3: 3, 6, 9 … 21. Using this counter, the surveyor could count the miles surveyed. Choosing the increment of 21 miles seems peculiar because 21 miles is not indicative of any land division in the U.S. Public Land Survey System. Of course when this counter was invented, the Public Land System was in its infancy, "An Ordinance for Ascertaining the Mode of Locating and Disposing of Lands in the Western Territory" was passed by the Continental Congress on May 20, 1785. (This "Ordinance of 1785" began what we know today as our system of sections, townships and ranges, or the U.S. Public Land Survey System.)

It seems that Goldsmith's less elaborately engraved and decorated compasses only have the one "P" (poles) outkeeper. His more extravagant compasses have both the intricate "P" outkeeper and the "M" counter.

As an accomplished clockmaker, artisan, mechanic, and craftsman, Chandlee's invention of the outkeeper should not be a surprise. What is surprising is that essentially no other makers copied and continued his elaborate "P" outkeeper. George Graves, Goldsmith's apprentice and successor, placed this same outkeeper in at least one of his compasses. Also, there is a compass by Goldsmith's son, Benjamin, that has this same "P" outkeeper. And, there is a compass plate by B.K. Hagger & Son, South Street, Baltimore (1824-1838) that has Chandlee's "P" outkeeper in the compass face. Unfortunately the form of the outkeeper digressed to the simple 1 through 16 dial that many makers adopted and placed on compasses into the 1940s.

Goldsmith Chandlee's "L" and "T" Table

All of the known Goldsmith Chandlee compasses except one have a peculiar "L" and "T" table on the south blade or limb of the compass. A facsimile is illustrated on page 26. < Only five other known compasses bear this table: one by Benjamin Chandlee (Goldsmith's son), two by George Graves (apprentice and then successor to Goldsmith Chandlee), an 1836 patent model (Patent No. 99) for a modified surveyor's compass by Francis Whiteley, and compass by B.K. Hagger & Son, South Street, Baltimore. These makers were all later than Goldsmith Chandlee. Whiteley was located in Stanardsville, Virginia in 1836. Stanardsville is only about 60 miles south of Winchester where first Goldsmith Chandlee (who died in 1821) and then George Graves produced compasses. Whiteley's patent model is made of brass, shows excellent workmanship, and is a working instrument. George Graves or someone else working for Chandlee probably made Whiteley's instrument and placed Chandlee's "L" and "T" table on it. No other makers who would have been contemporaries of Goldsmith Chandlee placed this table on their compasses. We can attribute this table to Goldsmith Chandlee, but what is the table's purpose?

Reviewing the literature of the period, in John Love's Geodaesia: or, The Art of Surveying and Measuring of Land Made Easie, 13th edition, 1796, there is a similar "L" and "T" table. A facsimile is illustrated on page 26.

In his discussion of Goldsmith Chandlee on page 27 of The Makers of Surveying Instruments in America Since 1700, Charles Smart "surmises" that "the linear table marked L and T refer to paces L (1-1/2 feet) and T to the number of paces 1 to 9." (Smart's 1-1/2 feet is a misprint—the first tabulated "L" is the number 2.5.) So, according to Smart, this table converts paces to feet using a multiple 2.5. This explanation seems weak for three reasons: 1) "L" and "T" don't seem indicative of feet and paces; 2) The conversion of 2.5 feet per pace may be nearly correct for some people, but certainly not all; and 3) What surveyor needs a conversion table to convert paces to feet anyway? We can discount Smart's explanation.

Some have hypothesized that the "L" and "T" is for computing offset for some angle or variation (see With Compass and Chain, by Silvio Bedini, pp. 375, 376). Benjamin Platt (1757-1833) used a "Lks." and "Var." table for that purpose (see pages 124-127 in Smart's book). Also for that purpose see Table VII, "Correction of Randoms—Links and Minutes of Arc" in Manual of Surveying Instructions for the Survey of the Public Lands of the United States, 1894. These tables serve a different purpose than Chandlee's "L" and "T" table.

A common calculation problem of the late 1700s and early 1800s was to survey or place on the ground a metes and bounds description given in perches and tenths of perches. (A perch or pole or rod are all the same, 16.5 feet.) The measuring device of the day being a chain, there arose the need to convert perches and tenths to chains and links. One perch is 16.5 feet or a quarter of a chain or 25 links. So, one-tenth of a perch is 2.5 links. Chandlee's "L" and "T" table is an exact conversion for that use. (Tenths of perches multiplied by 2.5 equals links.) For example: to measure off a distance of 18.5 perches, the surveyor would measure four whole chains (16 perches), then measure an additional chain (two perches for a total of 18), then he would look at the table to find the remaining 0.5 perches equals 12.5 links and he would have measured the desired 18.5 perches.

We have a peculiar "L" and "T" table with a contemporary explanation for its use published in Love's Geodaesia. We certainly can attribute its use to Goldsmith Chandlee.

Boundary retracement surveyors today practicing in the mid-Atlantic states who are familiar with the chains/links to perches/tenths conversion and vice versa (and make that conversion today) have no doubt as to the use of Chandlee's "L" and "T" table. It is just as John Love published, it converts links to tenths of perches.

The Six Quaker Clockmakers Book - By Edward Chadlee

In 1943 The Historical Society of Pennsylvania published The Six Quaker Clockmakers by Edward Chandlee, a descendant of the colonial clockmaker family. The book is chock full of information and pictures regarding the amazingly talented Chandlee Family that made clocks, surveying instruments, and other things from approximately 1760 thru 1825. The copyright protection has apparently expired on the book, so I have attached the Goldsmith Chandlee chapter below, along with pics of the surveying instruments and some of the clocks Goldsmith made featured in the book.

Mobile Device Users - You Must Open This Multi Page PDF By Clicking Here

Article #2

Additional Pictures

© 2020 Russ Uzes/Contact Me