Julius Hanks Minute Compass Dated 1821

Minute Compasses

Minute Compasses are a well kept secret. Dale Beeks told me about them a few months ago, and I quickly became fascinated by them. Dale has a long history with Minute Compasses, and he helped me create this webpage (Thanks Dale!).

Simply put, Minute Compass were a very early attempt at creating compasses that could measure angles more precisely using only a magnetic needle. They were High-Precision Compasses!

In Colonial America the vastness of the unsettled land generally meant that high precision wasn't required. Land was cheap, so buyers of land did not want to raise the price of acquiring land by buying expensive but precise surveys. Many of the compasses made, especially the wood compasses, filled the need for relatively cheap compasses that could measure angles accurately enough.

These more accurate readings transferred to a map or plat, would allow for more accurate placement of monuments and boundaries and more accurate closure of surveys.

Not surprisingly, there was likely a growing need over time for more accurate instruments. These more accurate readings transferred to a map or plat, would allow for more accurate placement of monuments and boundaries and more accurate closure of surveys. America contained a number of creative and mathematically inclined instrument makers and thinkers who considered how to make compasses more precise. The creative Colonists and Early Americans came up with a number of different ways to add more precision to a brass compass - to the point where you could read a compass from 1 to 15 minutes of a degree.

Minute Compasses are scarcely seen, and when they are seen, are often mistaken for Vernier Compasses. You will be able to spot them immediately once you know what to look for. They were the precise compasses of the day.

Dale has seen 3 different types of Minute Compasses, but there could be more variations out there. Please contact us if you have a Minute Compass, or know of a different type of Minute Compass.

The 3 types of known Minute Compasses are:

1. The Miller Minute Compass - Scale on Compass Face

2. The Patterson Minute Compass - Moveable Sight Vane

3. Needle Tip Vernier

As discussed below, it was also possible to use a vernier compass as a Minute Compass - a technique recommended by several textbook writers.

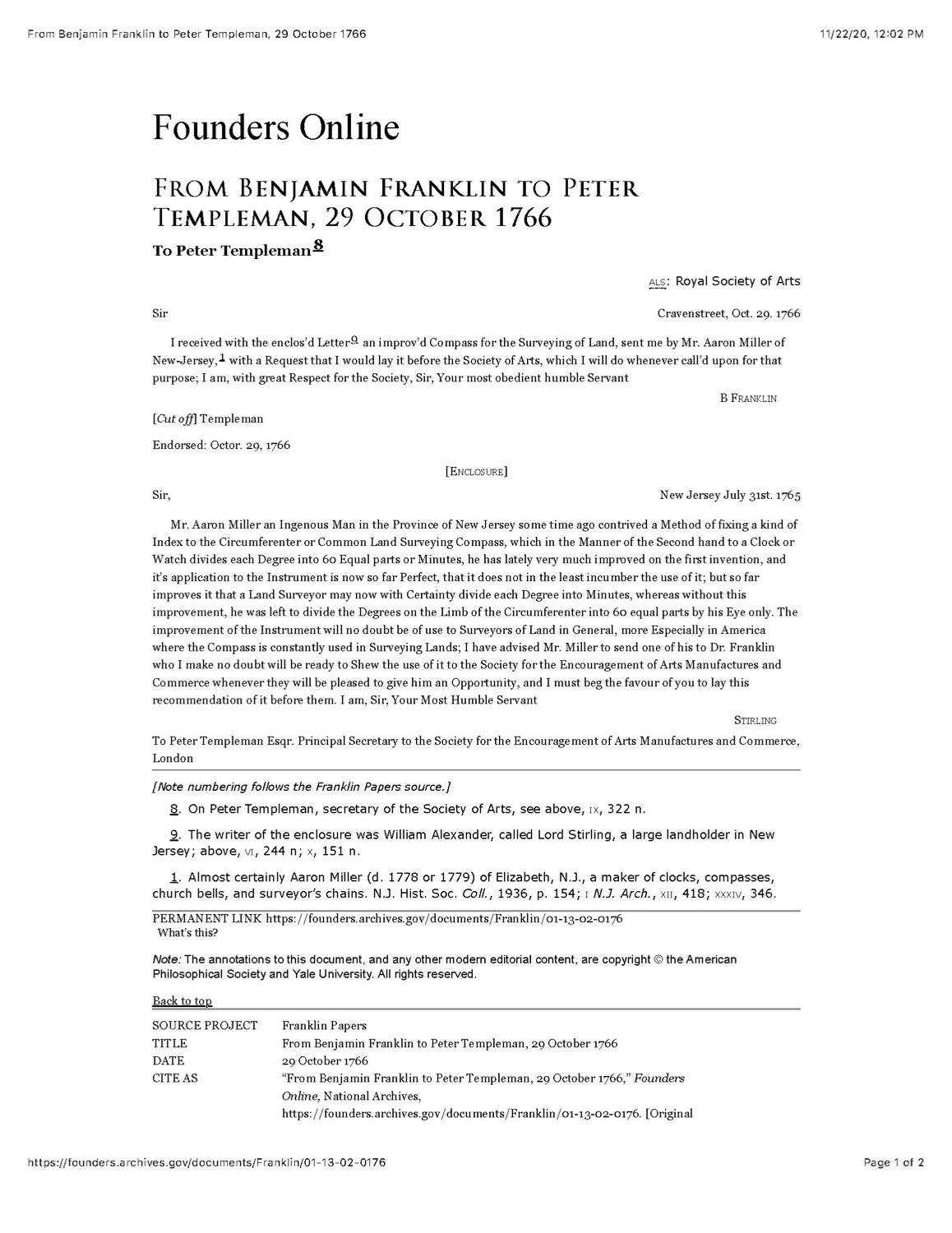

Minute Compass #1 - The Miller Internal Scale Minute Compass - Circa 1766

The first mention of a Minute Compass occurred in 1766 and involves Aaron Miller, a creative instrument maker, and Ben Franklin:

To date, nobody has found a Minute Compass made by Aaron Miller. While I have a Circa 1760 Miller Compass, it unfortunately is not a Minute Compass. I would love to find a Minute Compass made by Aaron Miller.

At least four different instrument makers made Miller-style Minute Compasses, however, and several examples are known to exist. The four known makers were Benjamin Hanks of Litchfield CT, Jospeh Farr of Pittsfield MA, Lebbeus Dod of Newark NJ, and Daniel Porter of Williamstown MA.

In use, a surveyor would set the tripod or staff with Miinute Compass, over a known point. The surveyor would turn an angle between the backsight and the foresight. After letting the needle settle motionless, the surveyor would read on the needle ring the approximate degree (unless the needle settled exactly on the degree mark). Using the minute compass functions, the surveyor would turn the plate from underneath until the needle settled directly over the degree mark. This shift translated to so many minutes on the minute-compass, readable on a 60 minute plus or minus semi-circle scale on the compass face.

Benjamin Hanks Minute Compass Circa 1785 - note the 60 degree plus or minus scale on the South end of the Compass. This compass is in the National Museum of American History.

This is a Circa 1790 Joseph Farr (Pittsfield) Minute Compass. Note the semi-circle dial at the top part of compass face. That's reads the degree in minutes when the compass operates as described above.

This is a Circa 1790 Lebbeus Dod (Newark) Minute Compass. As with the Farr compass to the right, note the semi-circle dial at the top part of compass face. That's reads the degree in single minutes when the compass operates as described above.

The National Museum of American History has an unsigned Miller Minute Compass that likely dated before the Revolutionary War. I have seen several other unsigned Minute Compasses offered for sale in old dealer catalogues. They looked very similar to this one.

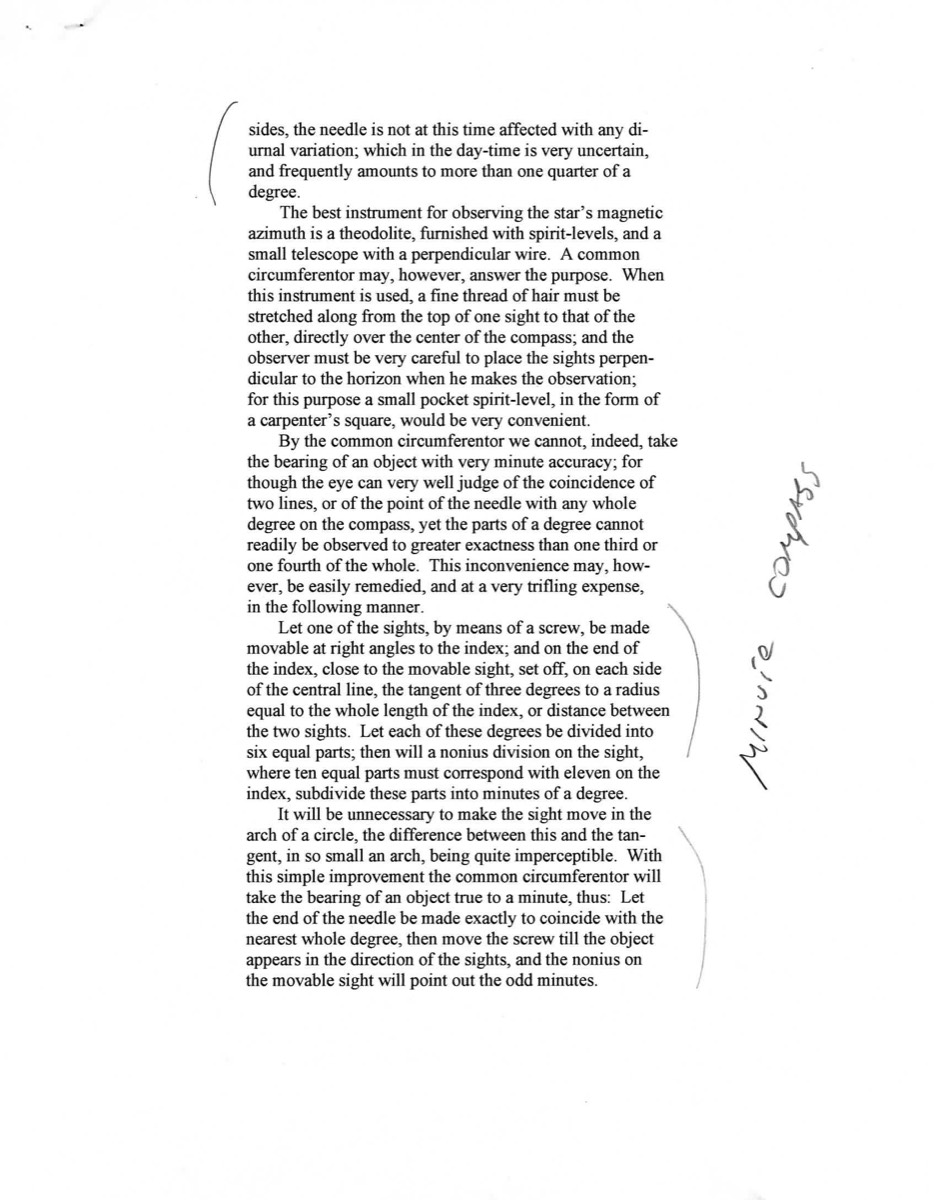

Minute Compass #2 - The Patterson Moveable Sight Vane Minute Compass - Circa 1786

The next mention of a Minute Compass pops up in The Transaction of American Philosophical Society in 1786, in an article published by Robert Patterson. See Below. In this article, Patterson describes how you can measure to a minute of a degree by making the South sight vane moveable. This is the approach taken by Julius Hanks with the picture at the top of this webpage.

Patterson describes his Minute Compass on the page below.

In use, a surveyor would set the tripod or staff with Minute Compass, over a known point. The surveyor would turn an angle between the backsight and the foresight. The surveyor would point the compass to the nearest degree line to the target (so the sights would not actually be in line with the target). The surveyor would then turn the screw on the moveable sight vane until the target lined up in the sight vanes. The surveyor could then read the vernier to see how many minutes the target was off the nearest degree line.

Julius Hanks is the only known maker of the Patterson Moveable Sight Vane. I tested the Hanks Minute Compass against two Gurley transits and aimed at targets about 100 years distant. The Hanks Minute Compass is amazingly accurate - the Hanks could measure objects that were 17 minutes of arc across, with the transits measuring basically the same arc. The Hanks compass was VERY sensitive to any movement, however, so the Hanks has to be absolutely immobilized when you are moving the South sight vane via the thumbscrew.

Attached below are two slightly different versions of the Hanks Minute Compass:

A Julius Hanks Minute Compass with a moveable sight vane. Note the placement of the screw mechanism. On this instrument the sight vane was built to sit on top of the screw, with part of the vernier scale built into the sight vane as well.

Another Julius Hanks Minute Compass with a moveable sight vane. Note the different placement of the screw mechanism. On this instrument the screw is fully exposed and is in-btween the sight vane and the vernier scale.

Minute Compass #3 - The Vernier on the Needle Minute Compass - Circa 1830s

The last known version of The Minute Compass apparently came out of Troy New York. This version puts a small vernier scale on the tip of the needle, and appears on some of Oscar Hanks' Bow Compasses. The Needle Tip Vernier also popped up recently on a newly-found Phelps Gurley Compass, which is pictured below.

The Needle Tip Vernier had one major advantage over the other versions of the Minute Compass - you didn't need to touch or move the compass to measure the minutes in-between the degrees. I found it very easy to upset the instrument by when I tested the other versions of the Minute Compass, which all required the surveyor to move or touch the instrument.

Using a Vernier Compass to Measure to Minutes

David Rittenhouse developed the first vernier compass in America in the 1760s. See the Vernier Compass Webpage. The original version of the Rittenhouse Vernier Compass had a vernier scale at the North end of the Compass, and you would turn the compass ring from underneath to account for the variation of the magnetic needle (e.g., 3 degrees East). The pic on the left is David Rittenhouse's Vernier Compass in the Smithsonian, while the pic on the right show a John Heilig Vernier Compass with the vernier scale on the South end of the Compass.

Based on the early textbooks I have seen, most surveyors in Early America only took the variation of the Magnetic Needle into account on resurveys of land (where they would need to figure out the and adjust for the change in variation from the original surveys to the time of the resurvey). I have also seen textbooks that advise a surveyor to use the vernier scale to measure angles like a Minute Compass would. The technique is basically this - you start with the vernier scale set to 0. When measuring an angle with the magnetic needle, let's say that the needle settles in between 39 degrees and 40 degrees. Using the Vernier adjustment system (e.g., tangent screw), you then rotate the compass box slightly so that the needle falls on the nearest degree, say 40 degrees. If the vernier scale shows that you moved 8 minutes, you would then know that the original needle reading was 39 degrees and 52 minutes.

My dad tested this approach out for the First Edition of his book, Chaining the Land (page 27). He said that while in theory you should be able to get to a single minute of accuracy with this approach, the best that he could do with this vernier compass was 3 to 5 minute of accuracy. Looks like he couldn't read the magnetic needle closely enough to get down to a single minute of accuracy.

This approach would be pretty unwieldy if you had the vernier set to adjust for variation at the same time, of course. After each measurement for minute accuracy, you would have to reset the compass for the variation. But, since early surveyors apparently didn't use the vernier often to account for Variation, they were free to use the vernier to provide more accuracy most of the time.

Looking at the pics below, it is interesting that the Rittenhouses put the vernier scale on the North end while Heilig put it on the South end. Based on the textbooks I have seen, I gather that most surveyors looked thru the South sight vane with the North sight vane out front. I wonder if a vernier on the South side might be more convenient to use for precise minute measurements? Maybe that's why Heilig put the vernier on the South side?

Circa 1790 John Heilig Vernier Compass

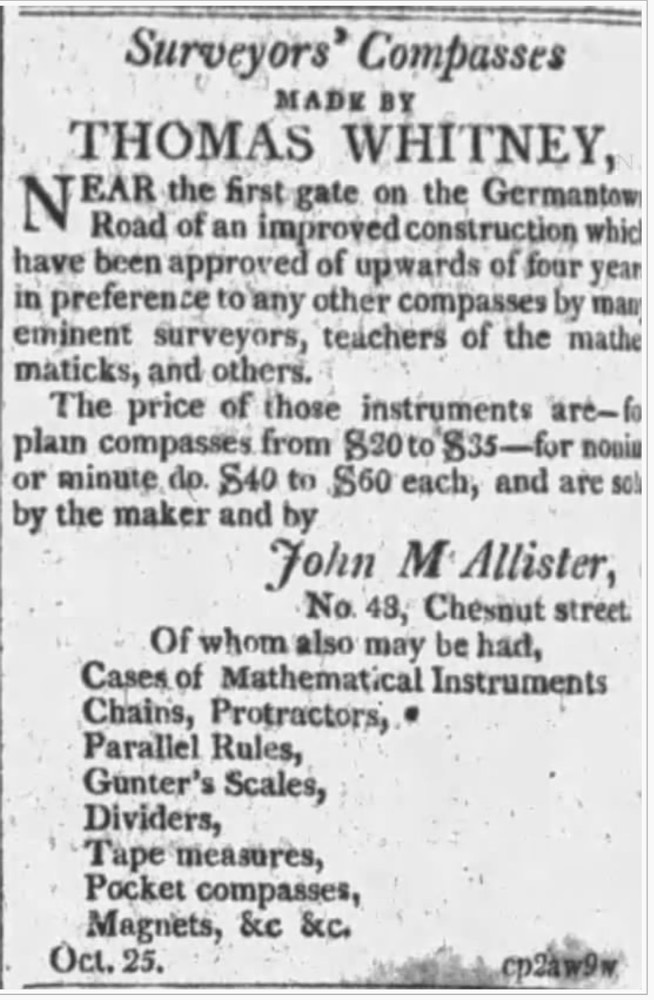

Another Philadelphia based maker, Thomas Whitney, advertised (thru McAllister) Minute Compasses for sale in an 1808 ad. But I'm not aware of any Whitney Minute Compasses in the forms shown above. So it is unclear whether Whitney's Minute Compasses differed from Vernier Compasses in any meaningful way. Interesting that Whitney's Vernier (noniuse) and Minute Compasses were priced the same. My best guess - Whitney had one standard design that could be used either in Vernier mode or Minute mode (or both modes, but that would entail moving the vernier mechanism constantly).

© 2020 Russ Uzes/Contact Me