Anthony Lamb Plain Compass - Circa 1730s

The Colonial Era of Compass Making

There were very few instrument makers in America during the very early Colonial period, so most of the early surveying instruments came from England. In the Northeast, Americans started making surveying compasses out out wood. Outside of the Northeast, America stated making its own brass instruments as English trained instruments makers, like Anthony Lamb, started to immigrate to America. These immigrants brought with them the skills and approaches used in England, so the earliest American brass compasses tend to look like their English cousins, but with allowances made for the local American market.

The Circa 1730 Anthony Lamb Compass made in New York pictured below is a perfect example of a very early American brass Surveying Compass. [The Anthony Lamb Story is a wonderful story, and you can read about it here.] First, note how the compass face contains two sets of rings. These are typical graduations for compasses made in England, and the first American makers were trained in England or followed the characteristics of the English makers. The American market didn't value the inner ring much apparently, so almost all of the American made compasses featured a much cleaner design with only the outer ring divided. The existence of an inner ring oftentimes suggests that the compass was made in England or by a maker trained in England.

Second, note how the sight arms extending on the North and South ends of the compass are a rather thin bar. The British limited the import of brass into America, so brass was expensive and maybe even hard to source. Makers tended to economize on the use of brass before the Revolutionary War. After the War makers were more generous in their use of brass.

Third, note how the sight vanes attach to the compass - thru slide-on dovetails. This is a neat early feature, but was not very secure and led to a loss of sight vanes. Knurled Screws and pinned vane bases replaced the dovetail system over time. Dovetails were rarely used if at all after 1800.

Fourth, note the use of the wing bolts. That's another very early look. Thumbscrews replaced the wing bolts early on.

Fifth, if you look closely, you will see that East and West are reversed on the Lamb compass face. Reversing East and West made it easier for surveyors to track bearings. David Rittenhouse is sometimes given credit for reversing East & West, but the 1730 Lamb compass clearly proves that the reversal happened well before David Rittenhouse came of age. The reversing of East and West is actually discussed in Love's book "Geodaesia" (1688).

Finally, note the engraving on the compass face. Many of the early Colonial Compasses were simply engraved with some notable exceptions - like compasses made by Anthony Lamb.

Two Lamb compasses side by side - Circa 1730s on the left and Circa 1760 to 1780 on the right. Note that East and West are reversed on the 1730's compass, but are not reversed in the later-made compass. Note how Lamb's engraving style grew much more precise and elegant as time passed.

Attached below are a couple of pics of a Circa 1750 compass made by Anthony Ham in Philadelphia. This compass economizes on brass as well - it's only 10 inches in length with a 4 inch needle. Like the Lamb, there is a single sheet of brass that serves as the compass base and sighting arms, and the Ham Compass also has slide-on sight vanes.

Attached below are a couple of pics of a Circa 1760 compass made by Aaron Miller in New Jersey. This compass is also pretty typical of the Colonial Period. Note again the very judicious use of brass. With the Lamb, there is a single sheet of brass that serves as the compass base and sighting arms, and the Miller Compass also has slide-on sight vanes. On the Miller Compass, the compass box sits atop a simple brass bar. Also note the sparse amount of engraving - the Miller Compass was a no frills brass compass. I suspect the levels were a later addition.

The makers in the Northeast part of Colonial America typically made compasses out of wood rather than brass. Please take a look at the Wood Compass Webpage. Wood was probably far cheaper and easier to access than brass in the Northeast. And perhaps the surveys didn't require much in the way of accuracy (wood compasses with printed compass cards were typically less accurate than engraved brass compasses). Whatever there reasons, wood compasses were fairly popular in the Northeast, and were made there until roughly 1825 or so.

How the Compass Evolved During the Colonial Period

In the 1760s and 1770s two creative makers, Aaron Miller and David Rittenhouse, developed ways to make the simple American Surveying Compass more accurate and easier to use. Aaron Miller developed a very innovative way to for compasses to measure to the nearest 5 minutes or less. David Rittenhouse developed a way to account for the variation in the magnetic needle (i.e., the vernier compass) and an automatic needle lifter.

Aaron Miller - The Minute Compass

In the early 1760s Aaron Miller created a way for a compass to measure to the nearest 5 minutes or less. Please see the Minute Compass Webpage for more information about this really cool innovation. In simple terms, however, Miller's Minute Compass involved rotating the compass box slightly to measure the number of minutes between (1) where the needle landed with the sights pointed at the target and (2) the nearest full degree division on the divided circle. Very clever. The pic below shows a 1795 Farr Compass using the Miller Minute Compass approach. Note the pointer that runs North and South, with the single divisions between 0 to 60 running on both sides of North and South. In the pic, the pointer is pointing to 5 minutes.

David Rittenhouse - Famous American - Vernier Compass

David Rittenhouse was an American astronomer, inventor, clockmaker, mathematician, surveyor, scientific instrument craftsman, and public official. Rittenhouse was a member of the American Philosophical Society and the first director of the United States Mint. Although not well-known today, David was a celebrity back in the day. To put this in perspective….The first three Presidents of the American Philosophical Society were in order Ben Franklin, David Rittenhouse, and Thomas Jefferson. David was simply a creative and skillful genius, and the surveying instruments he made reflected both his genius and skill.

David Rittenhouse created the idea of the Vernier Compass in America. Please see the Vernier Compass Webpage for more details. David's first version of the Vernier Compass had a small vernier scale located at the North End of the Compass. See the Pic attached below. You would rotate the compass box with a thumbscrew from below to match the Variation in the compass needle for your given location and time.

David Rittenhouse also invented the automatic needle lifter during the Colonial Era.

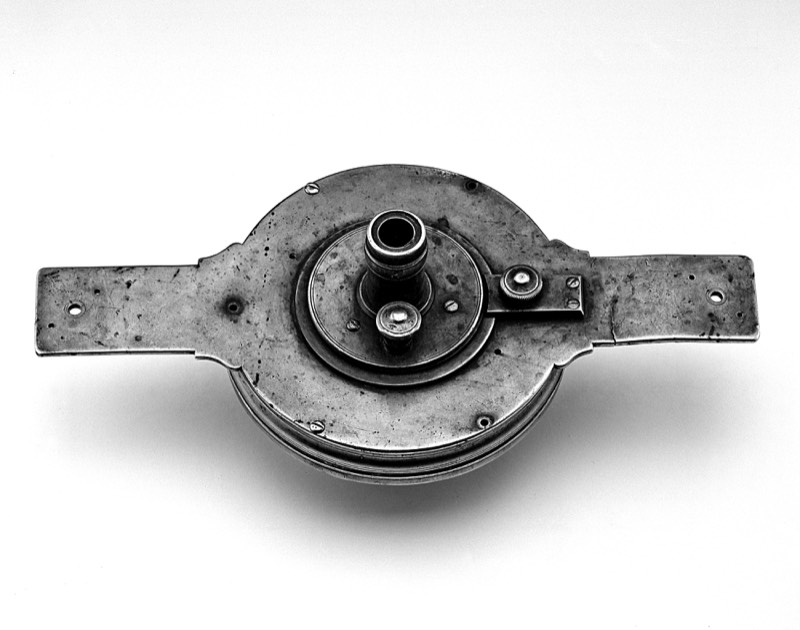

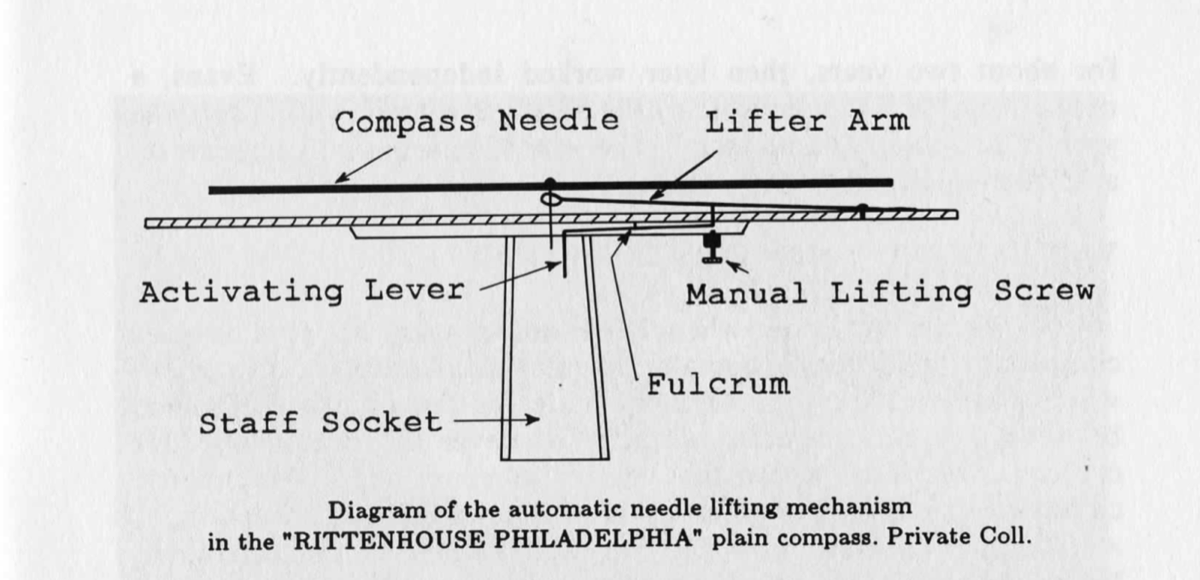

Note the picture showing the underneath the compass.

Please see the David Rittenhouse Webpage

To read more about the many creative ideas David Rittenhouse brought to surveying, see Uzes - Colonial Surveyor and Instrument Maker (1990) published in the Rittenhouse Journal (Vol 5, No 1).

David Rittenhouse - Automatic Needle Lifter

David Rittenhouse also invented the automatic needle lifter during the Colonial Era. This neat device saved wear and tear on the pin. The needle would only rest on the pin when the compass sat on top of a staff or tripod. See my dad's article cited above for a more detailed explanation.

© 2020 Russ Uzes/Contact Me